Matriarchs in India

Posted

“Nothing matters. She is the oldest in the family, it is her responsibility.” said my father once.

He is around sixty years old now. A kind, hardworking, and stubborn character. Yet, in all the words I could think of, progressive is not one I would use to describe him. He has his strong unchanging views on religion, work, and people that were made up a long time ago.

When he said the line quoted above, he was talking about a struggling family. The eldest sibling was a woman who was married, had children and was relatively better off. He was of the opinion that she had to fully commit to supporting her “actual family”, her parents and younger brother (who was an adult well into his 40s) as she is the eldest. There was no consideration for her married life.

When I was growing up, we were closer to our mom’s side of the family, not just emotionally but ritualistically as well. My surname was kept the same as my mother; it didn’t matter what my father’s surname was. When my maternal uncle died, by ritual I was one of the closest next of kin.

Therefore, I was supposed to do the funeral rites. As a child, none of these things ever seemed odd to me. This was my culture.

Marumakkathayam was a system of matrilineal inheritance prevalent in what is now Kerala, India.

Descent and the inheritance of property was traced through females. It was followed by all Nair castes, some of the Ambalavasis, Mappilas, and tribal groups.

Kerala’s caste system is as intricate as it is irksome. Complicated beyond belief, communalism was established so thoroughly that the verbiage differed for separate castes. You could be neighbours for generations but both of you would refer to the same thing with different words.

- Here’s a small example:

A Nambutiri’s (Sacred thread brahmin’s) house is called an “illam” and never referred to as a “vidu”, (literal translation of house) which most everyone else uses.

Turns out, Matriliny (Marumakkathayam) was abolished decades ago by law, but can you erase customs and culture solely by the stroke of a pen? That too in a state where historically, your ancestry was your sole identity?

What I saw, growing up in a different state, in a different era, were remnants of a long-forgotten matrilineal past.

For the uninitiated, this meant that Kerala at one point had small and large families (A huge taravad could have hundreds of family members) where the oldest female was the matriarch. Her husband, after marriage would live in her house and was not considered a part of her family. Her eldest brother would be a manager (karnavar) under her, her successors would be her daughters, and her sons would be married off to a suitable family. A maternal uncle held more importance than the father. The brother and sister bond was considered far more sacred.

Manu Pillai, in his fantastic book “The Ivory Throne”, writes, “The marriage system itself was something that never ceased to fascinate visitors to Kerala. This was simply called sambandham, or relationship, and as one distinguished observer noted, it was not seen as a sacred contract but as a purely fugitive alliance, terminable at will.”

I am a sceptic. I would have easily believed this to be recorded exceptions rather than the rule, but as luck would have it, my paternal grandfather was a Nambutiri Brahmin. He married (It was called a sambandham then, not marriage or kalyanam) my grandmother who was a Warrier (an Ambalavasi caste) and stayed at her house his entire life. This marriage happened somewhere around the 1930s with no pomp or even ceremony. Grandfather gave her a piece of cloth in front of a lamp and just moved in.

If that’s surprising, there’s more in the book about a time long before this. “Sexual freedom was also remarkable so that while polygamy was happily recognised in other parts of India, in Kerala women were allowed polyandry. Nair women could, if they wished, entertain more than one husband and, in the event of difficulties, were free to divorce without any social stigma. Widowhood was no catastrophic disaster and they were effectively at par with men when it came to sexual rights, with complete autonomy over their bodies.”

This is further supported in “A Survey of Kerala History” by A. Sreedhara Menon, when talking about life in the 16th and 17th centuries, “Women of the age enjoyed considerable freedom in society. The Nair women used to dress themselves in the best of clothes and adorn the most attractive ornaments and throng public places in the company of their men. They also followed the practice of polyandry without any social stigma being attached to their conduct.”

What is fascinating is that Royal families also followed the matrilineal tradition. The oldest male member was preferred to be the Maharajah but in case there wasn’t one of the right age yet, the mantle was handled by the eldest female. Even though the British only recognized these women as Regents, they were locally treated as, and were for all intents and purposes, a Maharajah. “What’s in a name?” you ask, well the proof is in the name. The last regent queen of Travancore state (The largest princely state in what is now Kerala), during her reign, had the name/title Pooradam Thirunal Sethu Lakshmi Bayi Maharaja, (Fyi, not even close to her full title :D).

Matrilineal inheritance is not new in India. We know of matrilineal customs in the Khasi tribe of Meghalaya as well, but this is on a completely different scale! An entire society where the position and freedom that women enjoyed were unparalleled. Just north of present-day Trivandrum lies Attingal. Attingal at one point in history was a queendom with incredible influence.

The female members were called the Attingal Ranis and the queendom was always run solely by the eldest female member. The title for this person was “Attingal mootha thampuran”. Just like the word “Maharajah”, “Thampuran” is also a masculine word. The feminine version would be “Thampuratti”, but in this society, it didn’t matter if it was a male or a female that sat on that seat; they deserved the same title, respect, authority, and autonomy.

This was not a ‘Hindu thing’ either. Manu Pillai writes, “In the Muslim royal family of Arakkal, women had equal rights of succession with male members of the house, ruling in their own right. Females of royal blood moved about freely in society, unencumbered by purdah and that severe seclusion that was their fate in other parts of India. They commanded tremendous respect, besides actively participating in affairs that were the strict preserve of men in less-inclusive societies."

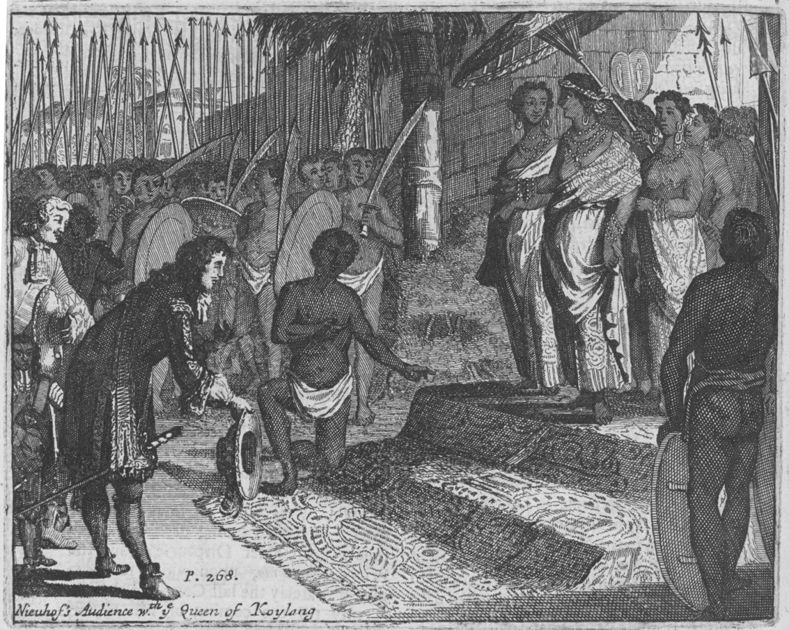

In 1591 when the Attingal queen’s relations soured with the Portugese, she along with her cousin sister (Queen of Quilon), raised an army of 20,000 men who all swore fealty to her, independent of any male influence. This is an example of the power these matriarchs possessed.

In the 18th century, with the rise of Marthanda Varma and his “Iron and Blood” policy of crushing the feudal elements, he shook hands with the British East India Company. Consequently, the British interference thereafter came with their ideas of morality, decency, and the roles men and women should play in a “civilized” society. They systematically broke down these, what could be now considered ’too good to be true’ practices with careful manipulation over decades, even centuries. By a twist of fate, we now look towards the west for contemporary examples of a more gender-equal society.

We burned all our allegiences from a disgraceful past, in the sacred-pyre that was the Independence Movement. Now, it seems like it’s time to sift through the ashes, and get inspired from memories that passed the test of fire.